Are you considering self-publishing a book?

If so, I’ve been in your shoes! I published the first novel in my sci-fan series back in 2018, and I remember all too well just how frustrating it was to research self-publishing options and still not feel fully informed about the decisions I was making.

Even when I thought I knew all I needed to know… I didn’t. I made some rookie mistakes that cost me money while I was operating on a very tight budget, and I learned that the self-publishing industry can be a little shady about hiding essential information in the fine print.

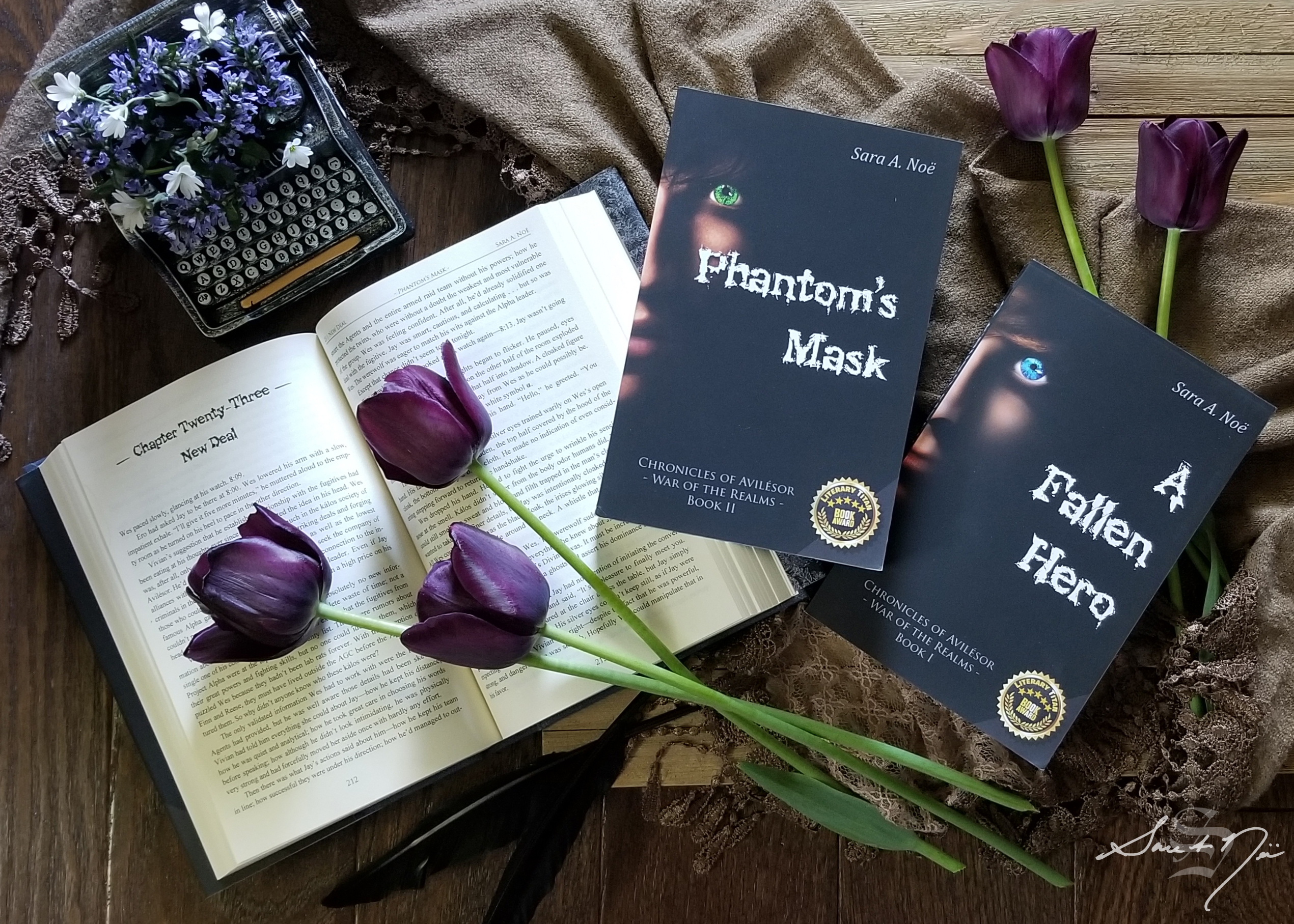

Now, I’m an award-winning indie author about to publish the third book in my series, and part of my mission on this blog is to help other aspiring authors by pulling back the curtains and sharing my experiences about self-publishing books. I hope that my articles help others avoid some of the pitfalls that tripped me up early in my career.

Below, I’ll dive deeper into eight important self-publishing facts that aren’t talked about enough. I learned some of these lessons the hard way by making errors, while others I stumbled across in my research and was shocked by how hard I had to hunt to find this critical information.

Introduction

- What Is Self-Publishing?

- Print-On-Demand (POD) vs. Traditional Print Runs

- What Is an Indie Author?

- What You Need to Know When It Comes to Self-Publishing a Book

- 1. You don’t need to buy an ISBN… But there’s a caveat.

- 2. Each book format and edition will need its own ISBN.

- 3. One ISBN cannot be used across different self-publishing platforms… with one exception.

- 4. Don’t waste your money on a barcode for your print books.

- 5. Royalties will be smaller than advertised when you’re self-publishing a book.

- 6. Amazon exclusivity prevents you from making bestseller lists.

- 7. You do not need to officially copyright your book prior to publication.

- 8. If you want bookstores to order copies of your novel, you must offer a return option.

What Is Self-Publishing?

Self-publishing is when every step of the publishing process, including editing, layout, cover design, ebook formatting, proofreading, marketing, et cetera, is done without the aid of a traditional publisher. All of the steps are done by the author or a freelancer hired by the author.

Print-On-Demand (POD) vs. Traditional Print Runs

Most self-publishing companies utilize a print-on-demand (POD) method in which a book’s metadata is available through retailers and distributors, but the physical copy of the book does not exist until someone places an order. Then, the exact number of books are printed to fulfill the order. This method cuts down on waste, eliminates storage needs, and minimizes the risk of printing books that don’t sell. However, the print cost per book is higher since there is no bulk discount.

In contrast, a traditional publishing house prints large quantities of books at a time. There’s no set number for a typical print run — a publisher weighs many factors and tries to estimate how many books they think they can sell based on the author’s established platform and market demand for the genre.

For hardcovers, a print run of 15,000 to 25,000 is considered good. For paperbacks, literary agents and publishing house editors tend to differ a bit more. An agent would consider 25,000 to be good and 50,000+ to be outstanding. Editors are usually more conservative, citing 15,000 trade paperbacks as a good print run and 30,000 as impressive.

What Is an Indie Author?

An independent author (aka “indie” for short) is an author who has self-published a book using their own resources without assistance from a publishing house. Self-publishing and independent publishing are used synonymously.

Indie authors can span across any genre, including fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Although an indie author doesn’t use an established publishing house, they do partner with a printer/distributor to produce their books and send them to retailers. Indie authors cover all editing and publishing costs out of their own pocket, whereas a publishing house takes on these expenses in the traditional publishing arrangement.

When self-publishing a book, the indie author maintains creative control over their work, including publishing rights and editing/design decisions. Traditional authors, on the other hand, sign the majority of those rights over to a publishing house in their contract.

What You Need to Know When It Comes to Self-Publishing a Book

Now that we’ve answered what is self-publishing, what is an indie author, and how does print-on-demand differ from traditional print runs, let’s dive into eight facts and hacks new authors need to know about self-publishing a book.

1. You don’t need to buy an ISBN… But there’s a caveat.

First… what is an ISBN?

ISBN stands for “International Standard Book Number.” It’s a 13-digital commercial book identifier that publishers, distributors, retailers, libraries, bookstores, and other supply chains use to find and order books. So… yeah, it’s pretty important and definitely something you’re going to need.

(Fun fact: if the ISBN was assigned before 2007, it’s only 10 digits.)

Depending on which self-publishing company you go with, you will likely have the option to use a free ISBN. I have personal experience with B&N Press, IngramSpark, and KDP, and all three reputable self-publishing companies offer the free ISBN option.

Your other alternative is to buy an ISBN from Bowker.

I know… why on earth would you buy an ISBN if self-publishing companies are giving them away for free?

It all depends on whether you want to be the official publisher. If you purchase your ISBN, then you (or your company if you created an LLC or are operating under a DBA) will be listed as the book’s publisher. If you use the free ISBN, the self-publishing company will be listed as the publisher, not you.

Also, if you use the free ISBN, you won’t be able to transfer it if you end up switching to a different self-publishing platform later. You would have to obtain a new ISBN for your book.

For me, I like to maintain as much creative control as possible, so I purchased my ISBNs. My LLC is listed as the publisher for my books. I don’t have to worry about any risks to my titles if something were to happen with IngramSpark since my ISBNs are directly from Bowker and could be transferred to another distributor if needed.

***Let me note that I do not have any direct affiliation with Bowker. I don’t earn any commission or credit if you decide you want to buy an ISBN.***

2. Each book format and edition will need its own ISBN.

This self-publishing fact isn’t as hard to find as others on this list, but it still sometimes takes new indie authors by surprise if they didn’t stumble across this information during their research.

Unless you’re strictly publishing an ebook, chances are you’re planning to offer your book in multiple formats (hardcover, paperback, ebook, audiobook, etc.) Each different format or media type needs its own identification number. If you release a second edition of your book, that will also need a new ISBN for every format.

With that in mind, Bowker’s 10-ISBN package is the smartest option for authors who want to purchase their ISBNs. It’s much cheaper per ISBN than it would be to buy the exact number of single ISBNs you need. Since they don’t expire, you can save them for future books or offer them to other authors (as long as they’re aware that YOU will be listed as the publisher since you bought the ISBN).

As of May 2022, here is Bowker’s ISBN pricing for U.S. authors/publishers:

If you’re interested in building your own publishing company, Bowker does offer larger ISBN packages so you can purchase in bulk and have plenty of ISBNs on hand to distribute to authors who pay for your publishing services.

3. One ISBN cannot be used across different self-publishing platforms… with one exception.

This was one of my biggest mistakes when I first self-published a book.

I did my research. I thought I had a decent grasp on the process and what I needed to do. I knew that I would need three ISBNs to cover my hardcover, paperback, and ebook formats.

What I didn’t realize was that I couldn’t use the same ISBN for each format — even though it was the exact same book — on two different self-publishing platforms. To my knowledge, there’s only one exception to this rule (which I’ll discuss in a moment). First, let me explain what I did wrong.

My original plan was to publish with B&N Press to tap into Barnes & Noble’s market. B&N Press was free, plus I anticipated that having the well-known name behind me would be a selling point so I could say that I’d published directly through Barnes & Noble (instead of copping to being an indie author upfront and battling the attached stigma of a low-quality, unedited book).

Then, after finalizing the proof copies and getting a few book signings under my belt, I intended to add IngramSpark’s distribution network so I could expand my reach into Amazon’s market and make the novel accessible to other bookstores, libraries, and global retailers.

My strategy was flawed from the very beginning.

First, my experience with B&N Press was awful. Their customer service was a nightmare, and with no phone number, my only way to communicate was through email. It was a rough navigation through my first few months of being an indie author with very little support from my printer/distributor. You can read my head-to-head comparison of B&N Press vs. IngramSpark here in this post.

Second, I knew B&N Press was restricted to Barnes & Noble’s network. What I didn’t realize was that IngramSpark doesn’t allow you to pick and choose which retailers carry your book. Except for the Apple and Amazon addendums, IngramSpark is basically all or nothing as far as distribution goes.

Which means… once I added IngramSpark, I had no way to opt out of Barnes & Noble and let B&N Press manage those orders.

Here’s where the mess really started. When I tried to set my title up on IngramSpark, my ISBNs were invalid because they were already in use with B&N Press. I ended up using two extra ISBNs from my pack of ten so I could register the paperback and ebook with IngramSpark while B&N Press was still managing orders in their own network. Instead of using the anticipated three ISBNs for three book formats, I was using five.

I’ve seen sources recommend creating a separate account for every platform you want to be on. One for KDP (Amazon), one for Apple, one for Barnes & Noble, and on down the list. The rationale is that you’ll get higher royalties that way as opposed to managing every channel from a wide distributor like IngramSpark.

But for that to happen, you’ll either need to buy a lot of ISBNs, or you’ll have to use the free ISBNs and surrender your title as publisher (not to mention manage a long list of ISBNs for the same title on each individual platform, all with different dashboards and self-contained sales tracking).

Once my book went live on IngramSpark, I soon realized another issue — I had duplicate listings on Barnes & Noble’s website. Since I couldn’t turn off IngramSpark’s Barnes & Noble distribution, both B&N Press and IngramSpark had live versions of the same book under different ISBNs.

I asked B&N Press if there was any benefit in sticking with their company while I was with IngramSpark. Their answer?

Well… your book is on our website twice.

Except that’s NOT a positive! Two listings meant that my book reviews were divided depending on which version someone reviewed.

Reviews help potential readers decide whether to invest in a book. More good reviews = more faith that your book will be worth the chance. Therefore, it’s a lot better to have one listing with ten reviews than it is to have two listings with five reviews each since a website visitor would likely see only one listing (they wouldn’t think to look for a second one with different reviews on it).

I was going to leave the hardcover as a B&N Press exclusive and let IngramSpark have the paperback and ebook, but by this time, I’d had enough of Barnes & Noble. I’d had nothing but issues, delays, misprints, and poor communication, and I was done.

I learned that I could transfer a title, which I did with my hardcover. But for the paperback and ebook, it was too late. I’d burned two perfectly good ISBNs by putting those formats on both IngramSpark and B&N Press at the same time. That error cost me $60 in ISBNs I could have used when the sequel was published a year and a half later.

Lesson learned the hard way — If you’re using two or more self-publishing book companies, you can’t share ISBNs across platforms even if the title is exactly the same.

However… I did mention an exception.

KDP + IngramSpark

IngramSpark and KDP have a unique partnership that bypasses this rule if you want to use those two self-publishing companies in tandem. KDP manages all of the Amazon orders while IngramSpark manages everything else in their global network, so it’s the best of both worlds. (This is what I thought would happen with B&N Press, but I was sorely mistaken.)

I’ll note that you do have to own your ISBN for this to work; you can’t use the free ISBNs provided by either company. You also can’t choose KDP’s expanded distribution option.

To my knowledge, this is the only exception to the ISBN rule. B&N Press and IngramSpark were not compatible, but KDP and IngramSpark are. (If I’m wrong and you know of another exception, please let me know in the comments!)

For more information on how to use IngramSpark and KDP together, check out this article on IngramSpark’s blog.

I will also say that I did NOT end up using this partnership, although I came close and even had my paperback set up in KDP and ready to go. Unfortunately, when I received the proof copy from KDP, I realized that it was much lower quality than my IngramSpark prints.

The award medallion on my cover was blurry (even though it was crystal clear in the digital file and on IngramSpark’s covers), my interior margins were shifted up higher on the page when they should have been centered, the glue on the binding was thick, and the ink on the pages was lighter, making the words harder to read.

In the comparison photos below, the KDP proof is on the left and IngramSpark’s paperback is on the right.

That’s not to say IngramSpark is perfect. I’ve had misprints that they’ve had to replace. But the quality of my book was noticeably lower from KDP.

Other authors I’ve spoken with have sworn that the quality of their books is equal between the two printers, but that was not my experience. I use KDP for my ebooks only. No print books.

If you’re considering using Ingramspark and KDP together for your paperbacks, I definitely recommend getting a proof copy from each printer to verify the quality is what you want/expect.

4. Don’t waste your money on a barcode for your print books.

If you decide you want to buy you ISBNs, you’ll also have the option to buy a barcode. The barcode is added to the back of the book so retailers and libraries can quickly scan the ISBN and retrieve the metadata without having to plug that 13-digit number manually into their system.

I don’t know why this isn’t clearly communicated, but let me say it bluntly: YOU DO NOT NEED TO PURCHASE A BARCODE WITH YOUR ISBN.

Let me prove it, because once again, I learned this lesson the hard way. Below, you’ll see the back end of my account in Bowker showing my titles and assigned ISBNs:

You’ll notice a few anomalies there in the dashboard — the results of my early blunders when I was new to self-publishing. First, my title A Fallen Hero has duplicates. It has one hardback, two paperback, and two ebook ISBNs.

Why the double ISBNs for the same title/format?

I mentioned earlier than I accidentally burned two of them because I didn’t understand that you can’t use the same ISBN on different self-publishing platforms. Since I temporarily had my paperback and ebook on both B&N Press AND IngramSpark at the same time (and therefore needed separate ISBNs for each format/platform), those original B&N Press ISBNs are basically duds now. Once a title is published under an ISBN, that number can’t be reassigned to a different book.

Second, the first two titles say “Manage” under the barcode column, while the rest say “Buy Barcode.” If you hadn’t guessed… it’s because I pulled another rookie move and purchased barcodes for those first two ISBNs even though I didn’t need to (which I figured out later).

See what I mean by indie authors needing to do a lot of extra research to hunt for information that isn’t clearly communicated? Looking at my ISBNs in Bowker, it sure looks like you’re supposed to buy a barcode for each one (at least the print formats), doesn’t it?

Trust me — you don’t! And I can show you.

Here is the digital file I submitted to IngramSpark for my paperback:

Notice that although I left a blank space for the barcode on the back cover, I didn’t purchase and download one of my own. Below is a photo of the back of my book:

IngramSpark supplied the barcode all on their own. And, if you scroll back up to my Bowker dashboard, you can see that ISBN 978-1-7325998-3-3 still shows “Buy Barcode” under its barcode status.

So, again — don’t waste your money on barcodes when you’re self-publishing a book! It’s very misleading in Bowker’s dashboard, but I haven’t purchased a barcode for any of my other titles, and it’s never been a problem.

5. Royalties will be smaller than advertised when you’re self-publishing a book.

This is a particularly frustrating pain point. For authors who are considering the pros and cons of self-publishing vs. traditional publishing, royalty percentages are likely one of the top factors guiding their decision.

As a general rule, you can expect to earn 10-20% royalties if your book goes through a traditional publishing house. Now, keep in mind that 20% is extremely generous and highly unlikely if you’re a newbie without an established fan base to guarantee high sales. New authors are more likely to get 10%.

Also remember that if you have an agent, s/he will skim an extra percentage off the top of your share.

All of the self-publishing companies I’ve encountered advertise more than 50% royalties for print books. B&N Press promises 55%, while KDP offers 60%. For IngramSpark, it depends on what you set your wholesale discount since you have control over that percentage, but you can go as low as 35% (meaning you get 65%… in theory).

I still remember someone once explaining the difference to me in terms of pizza. A traditional publishing house positions you to sell a LOT more books but at a lower royalty cut, whereas self-publishing a book gives you higher royalties on fewer sales. So, would you rather have 10% of an entire pizza, or 60% of a single slice?

Except… that’s not really how it works.

Self-publishing companies are finally getting better about being more upfront and making it clear that the print cost will be subtracted from your royalties.

But what they DON’T do is give potential new indie authors a great idea of what that breakdown really looks like. When you subtract that print cost out of your percentage and do the math, you’ll probably be bringing in somewhere between 15-30% profits from the retail price a customer paid for your book.

That paints a very different picture than the “Earn 60% royalties when you self-publish with our company!” marketing pitch.

Think about it — if you’re trying to decide between independent and traditional publishing, and you know that traditional publishing will bring in MUCH higher book sales… a royalty cut of 10-20% isn’t really that much smaller than 15-30%, is it? The pizza analogy is a lot less impressive when you’re debating about 10% of a whole pizza versus 20% of a single slice (instead of 60%).

A traditional publishing house covers the print cost (plus other costs like editing and formatting that get transferred to indie authors), so as far as a royalty breakdown, you’re basically comparing apples to apples now. Other factors, like maintaining creative control, become much more important to drive your decision about which publishing model you want to use.

(Friendly reminder that for traditional publishing, you won’t start earning royalties until the publisher has recouped your advance that was paid upfront.)

Example

To demonstrate royalties for an indie author, I’m going to be completely transparent and give you a real breakdown of the numbers for my first paperback distributed through IngramSpark.

I set my retail price at $19.99 with a wholesale discount of 40%. (Note: IngramSpark allows you to choose between 35-55%, but they warn you that retailers might not buy your book if your discount is too low. When I first published as a brand-new author with no clout behind my name, I had it set at 50%. After the book secured good reviews and won an award, I felt confident that wholesalers would still be willing to order copies with a reduced discount, so I lowered it. Not all self-publishing companies give you this freedom to set your own wholesale discounts.)

Chances are, $19.99 isn’t the retail price you’ll see on Amazon because Amazon (and any book seller, really) can do whatever they want and set the price however high or low they see fit. It doesn’t matter for me because they still bought it from IngramSpark at 40% off $19.99, so they paid about $12 for the book. Whether they resell that book at $12 or $50, that doesn’t change the cost of their purchase from IngramSpark based on the suggested retail price and wholesale discount I set. As far as the author is concerned, that book has already been paid for.

$12 per book seems like a great deal for the author, doesn’t it?

It would be! If that’s how the process actually worked.

Print costs have, unfortunately, increased recently thanks to inflation, supply chain issues, higher shipping costs, materials, and the list goes on. At the moment, my cost to print one 468-page paperback is $7.83. (Your print cost will be different — it’s dependent on page count, interior illustrations, cover type, book size, etc.)

When you subtract $7.83 from $12.00, I’m actually earning $4.17 per book. So really, instead of pocketing 60% royalties (as advertised), I’m taking home just under 21%. Still better than what I’d likely see from a traditional publisher, but nowhere near what I initially anticipated based on how self-publishing companies advertise their royalties for indie authors.

Ebook royalties are generally more straightforward since there is no print cost to factor in, although KDP is the only platform to charge a “delivery fee” for ebooks. Gotta pay attention to the fine print when you’re self-publishing a book!

6. Amazon exclusivity prevents you from making bestseller lists.

This tidbit came as a surprise. If you’ve been researching your self-publishing options, chances are you’ve had your eye on Amazon.

If not, you definitely should because Amazon still holds a monopoly on the book market. So much so, in fact, that that Association of American Publishers (AAP) filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 2019. In their letter, they asserted that:

“The New York Times reported that Amazon controlled 50 percent of all book distribution, but for some industry suppliers, the actual figure may be much higher, with Amazon accounting for more than 70 or 80 percent of sales.”

Source

So, here’s the deal. As an indie author, you DEFINITELY want your book to be on Amazon. There’s no question about that. It’s one of many reasons I left B&N Press, because their distribution model was restricted to only Barnes & Noble.

The real question is, do you want to be exclusively on Amazon?

That’s a hot-button debate in the indie author community. Some authors lock themselves into exclusivity contracts with Amazon to get higher royalties, marketing advantages, Kindle countdown deals, free promotions, and other benefits. That’s where the majority of the U.S. book market is, so why not direct all of your focus there? (Note: Amazon’s hold isn’t so dominating in the global market, so it also depends on where you want to sell your books.)

Me… I’m a don’t-put-all-of-your-eggs-in-one-basket kinda woman. If the monopoly ever topples, what will happen to those books?

That, and I simply don’t trust Amazon. Here are some of the reasons I’m incredibly wary about Amazon exclusivity:

Amazon has a history of screwing over authors.

I’ve actually talked to some of those authors firsthand when I was doing my initial self-publishing research. Amazon is subject to change their policies and royalties on a whim, sometimes booting authors out of KDP for bogus violations with no way to get back in. The “transgression” could be as simple as forgetting that you’d set up an Amazon account under a different email ten years ago.

For authors who built their entire marketing platform and fan base on Amazon, being expunged from KDP is a big problem. Some of the authors I spoke with didn’t even get their final royalty payment. What are you going to do? Take Amazon to court? Good luck.

Have you ever heard of Audiblegate? A reporting error in October 2020 revealed that Amazon’s “easy exchange and return” policy allowed customers to buy an audiobook, then “return” the digital download for a refund or swap it out for another audiobook at any time. But Audible didn’t foot those refunds or pay any royalties on the swapped audiobooks. If an audiobook was returned, even if the consumer had already listened to it in its entirety, Audible deducted that money from the author, publisher or narrator — the victims who were unknowingly funding that exchange/return program at their own loss while Amazon didn’t lose a penny.

The point is, Amazon has some shady practices that really hurt authors. My mistrust isn’t unwarranted.

Most bookstores turn down Amazon-printed books.

I learned early in my research that if you are exclusive to Amazon, you will have a MUCH harder time convincing bookstores to carry your novel on the shelf. This knowledge was only further cemented after I published and started approaching bookstores myself. Many of them have a strict no-Amazon policy. Which makes sense, if you think about it. Amazon is their #1 competitor taking away book sales… why would they want to order Amazon books and support their competition?

(That, and Amazon books don’t have the best reputation because KDP is completely free, which means authors have been known to push out low-quality, unedited books simply because it was free and easy. That’s certainly not to say that all Amazon books are bad, but this was an issue early on when CreateSpace was still around, and it’s a bad rep that’s stuck around even though KDP has buckled down on books that are riddled with typos and errors.)

Here’s a disclaimer I found prominently displayed on a Chicago bookstore’s website:

“We do not order Createspace or any Amazon affiliated printers. Honestly, we don’t even take Createspace printed books. The ONLY rare exception is for regular customers/neighbors/books specifically about our neighborhood. Even then, we will probably lecture you on life choices and point you towards IngramSpark for your future printing.”

Amazon exclusivity in KDP Select can be good for certain authors, but it also has some serious cons to consider.

I went with the wide distribution model to make my books, ebooks, and upcoming audiobook accessible for readers and libraries across just about any platform. But, when I transferred my Kindle ebooks from IngramSpark to KDP (still leaving my other ebooks with IngramSpark so they would be on Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Apple, etc.), Amazon encouraged me to sign up for KDP Select, which is the author program for Amazon exclusivity in Kindle Unlimited (KU).

Some authors swear that KU is the way to go, but I wanted to do some research before committing. Here’s what I learned:

First, author payments are handled very differently. Rather than getting paid for a download of your ebook, Amazon sets aside a pot of money collected from KU subscribers every month. This is called the KDP Global Fund. This pot is divided among all the authors enrolled in Kindle Unlimited as a percentage based on how many pages of your book(s) were read during the month.

The more pages KU subscribers read, the more you make. So, you would earn the same amount if two people each read 500 pages as you would if 1,000 people read one page. Only the page count, not the number of readers, affects your earnings. The payout is usually just under half a cent per page, but it’s dependent on the global fund.

For rapid-release publishers with a lot of titles and an enthusiastic fan base devouring your content, KU could be a profitable avenue for you. If it takes you a year or more between releases (like me), you’ll be hard pressed to make Kindle Unlimited become a reliable source of income.

Second, traditional publishers do not use Kindle Unlimited. Readers won’t find bestsellers from Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, or Macmillan in KU. All of the books available in Kindle Unlimited are published by indie authors and small presses. That’s not necessarily an issue if readers don’t mind not having access to the bestselling books coming out of the Big Five, but for me, I wanted my novels to be on par with traditionally published books and compete at the same level, so I wanted to be where they were.

Third — and this one’s the real kicker — it’s already very difficult for indie authors to hit bestseller lists like the New York Times and USA Today lists. But many of those bestseller lists, including the two I just mentioned, require books to be available through a minimum of two retailers. Which means if you give Amazon exclusivity, you disqualify yourself from even being considered on those bestseller lists.

When I learned that, I couldn’t believe it wasn’t common knowledge! For new authors who are learning how to self-publish a book, that information is important to help them make distribution decisions, especially if they’d always aspired to add USA Today Bestselling Author to their title someday.

7. You do not need to officially copyright your book prior to publication.

“Do I need to copyright my manuscript before I self-publish the book?” is a common question new indie authors ask.

The technical answer to this question is no. The subjective answer is… it depends on your situation and comfort level.

According to the U.S. Copyright Office, “Your work is under copyright protection the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form that it is perceptible either directly or with the aid of a machine or device… In general, registration is voluntary. Copyright exists from the moment the work is created. You will have to register, however, if you wish to bring a lawsuit for infringement of a U.S. work.”

Technically, you are the legal owner of the content once it’s in a tangible, shareable form, even if it’s not officially registered through the Electronic Copyright Office (eCo). You don’t need to copyright your manuscript prior to self-publishing a book.

BUT, that being said, paying a small copyright fee might not be a bad idea for peace of mind, especially if you plan to send your manuscript out to beta readers, literary agents, publishers, editors, and freelancers you don’t know on a personal basis.

I know an author who periodically shared parts of her WIP (work in progress) in a social media group of writers for feedback, only to discover that one of those members copied her plot and made minor tweaks to her characters, then rushed to publish the knockoff book before she could publish her original story. Her situation is every author’s nightmare (and it’s one of the reasons I’ve always been very careful about how much of my WIPs I share on social media).

For me, I chose to copyright my first novel. My original intention had been to publish traditionally, not independently, and I wanted to make sure I had an iron-clad legal defense if an unethical literary agent or publisher stole my work. I felt more secure knowing that I could prove the story was mine if the need ever arose.

However, now that I’m publishing my third novel in the series, I don’t plan to officially copyright the manuscript through the U.S. Copyright Office. My creative content has been well established by this point with the same characters and settings in the first two books. It’s clearly my work; there’s no need to pay for the extra protection.

When I break away from the Chronicles of Avilésor series someday and publish brand-new material outside of this fantasy world, I will likely go back to copyrighting the first novel at a minimum in each new series. It’s not necessary, but it makes me feel safer from a legal standpoint to protect my work if I ever find myself in court fighting to prove that I am the rightful owner of my content.

For more information about copyrighting your book, check out the official copyright.gov FAQ page for more information

8. If you want bookstores to order copies of your novel, you must offer a return option.

I learned this lesson during my awkward shift between B&N Press and IngramSpark… and in the most unusual circumstance.

In 2019, when I was still in the middle of figuring out how to get my titles over to IngramSpark, I did a Barnes & Noble book signing tour that took me to seven cities in three states. (Pro tip: you don’t have to publish through B&N Press to do this. It’s not an exclusive perk — you can set these signings up yourself just by calling, emailing, or going into stores and asking to schedule an event. Some will turn you down. Some will say yes.)

Each Barnes & Noble store acted independently. Some of them expected me to bring the books with me for a consignment agreement, then take home any extras that didn’t sell. Others were willing to pay the wholesale price and order their own copies into the store, then keep the extras on the shelf after I left.

But here’s where I learned a fascinating lesson. Barnes & Noble store managers were willing to order copies from IngramSpark, but not from B&N Press.

Yep, you read that correctly. I’ll say it again — Barnes & Noble stores would not order my books printed in their company’s own press. But they would buy them from a self-publishing competitor.

Why?

Returns.

B&N Press books were not returnable, which meant if they didn’t sell, the store was stuck with the inventory. IngramSpark books, on the other hand, give the author a choice to make the books returnable or not. Since my IngramSpark copies were returnable, store managers were willing to risk placing an order since they could send back the extra books if needed.

Crazy, right?

So, based on my own personal experience, I HIGHLY recommend you choose a self-publishing company that allows returns if you plan on approaching bookstores to carry your novel. This lesson has been consistent across the board with many independent bookstores too, not just Barnes & Noble.

If you use IngramSpark for distribution, you’ll have two return options.

Option One: Yes – Deliver

The copies will be shipped to you regardless of the condition they’re in, so they may or may not be resalable. Keep in mind that in addition to covering the wholesale price of the books, you’ll also be responsible for any shipping and handling fees, so this option can potentially be expensive. It’s only for books sold in the United States or Canada.

Option Two: Yes – Destroy

Returned copies go back to Ingram’s facility where they are recycled. Your only charge is the wholesale cost of the books, so there aren’t any extra shipping and handling fees. It’s a more economical option (if you’re okay with the thought of your books being destroyed).

Final Thoughts on Self-Publishing a Book

There’s a LOT of work that goes into self-publishing a book. There will probably be moments when you want to scream and pull your hair out.

Like I said, I’ve been there myself. Multiple times. But I promise, it gets easier every time you publish a new book. You’ll figure out the learning curve. And let me tell you, there is no feeling in the world quite like holding your published book in your hands for the very first time!

While you’ll no doubt learn from your own mistakes, I hope you’ll also learn from mine so you can avoid some of those pitfalls I fell into. After all, that’s why I write these posts! Several indie authors gave me advice and guided me early in my career, so I enjoy paying it forward and putting this information out into the world to help other indie authors starting their journey.

If you found value in this article and would like to show your support, please consider buying me a drink, subscribing to my newsletter, and/or checking out my award-winning sci-fan series!

Still on the fence about whether you want to publish independently or traditionally? Check out some of my other posts:

- 3 Reasons Why I Self-Published

- Pros & Cons: Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing

- 15 Tips to Write a Compelling Fiction Blurb That Sells

- How to Make Money: 7 Extra Revenue Streams for Indie Authors

- Self-Publishing Review: Barnes & Noble Press vs. IngramSpark

- IngramSpark Self-Publishing: Process, Royalties, Review, & Advice

- NetGalley Co-Op Review with Victory Editing

- Should Authors Publish Under Their Real Name or a Pseudonym?

I'm an award-winning fantasy author, artist, and photographer from La Porte, Indiana. My poetry, short fiction, and memoir works have been featured in various anthologies and journals since 2005, and several of my poems are available in the Indiana Poetry Archives. The first three novels in my Chronicles of Avilésor: War of the Realms series have received awards from Literary Titan.

After some time working as a freelance writer, I was shocked by how many website articles are actually written by paid "ghost writers" but published under the byline of a different author. It was a jolt seeing my articles presented as if they were written by a high-profile CEO or an industry expert with decades of experience. I'll be honest; it felt slimy and dishonest. I had none of the credentials readers assumed the author of the article actually had. Ghost writing is a perfectly legal, astonishingly common practice, and now, AI has entered the playing field to further muddy the waters. It's hard to trust who (or what) actually wrote the content you'll read online these days.

That's not the case here at On The Cobblestone Road. I do not and never will pay a ghost writer, then slap my name on their work as if I'd written it. This website is 100% authentic. No outsourcing. No ghost writing. No AI-generated content. It's just me... as it should be.

If you would like to support my work, check out the Support The Creator page for more information. Thank you for finding my website! 🖤