I was a junior in high school when I gave my first full-length fantasy novel, Shadow Rider, to two of my favorite English teachers to read over summer vacation, then nervously awaited their feedback.

One day, my teacher asked me to come to his classroom after school to discuss the manuscript. My stomach was in knots. I braced myself to have my hopes dashed and hear him tell me that I wasn’t cut out to be an author.

To my absolute relief, he said that he’d enjoyed the story immensely and was impressed with the depth of the world I’d built, and that he looked forward to reading the published book someday.

Stuck to the top page of the manuscript was a sticky note that read, “Look up Tolkien’s primary and secondary worlds.”

He pointed to the note and asked me, “Are you familiar with Tolkien?”

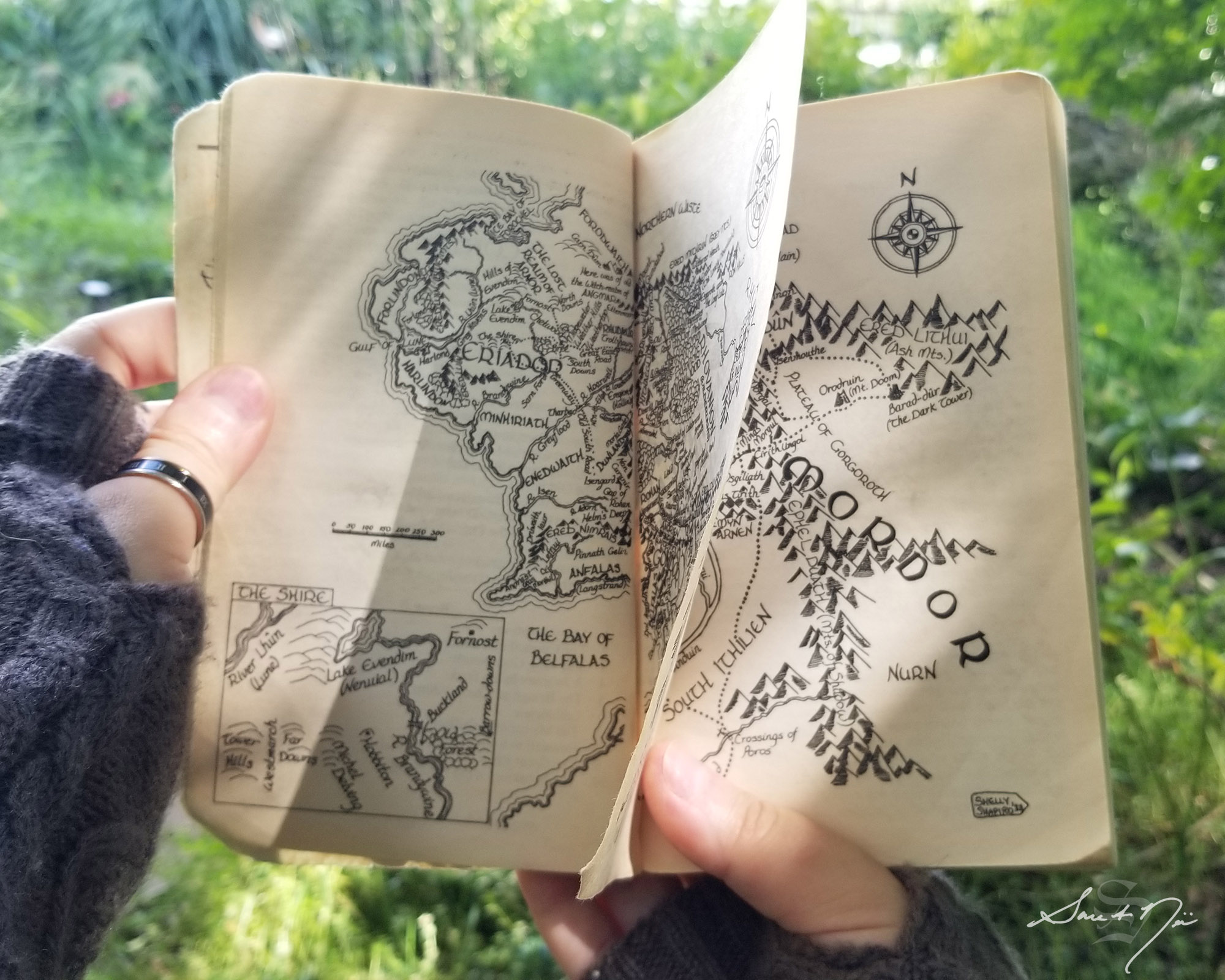

“Yes,” I said, nodding and thinking of my tattered, badly beaten (aka well-loved) paperbacks of the Lord of the Rings series that had been carried in my backpack throughout middle school.

“Are you familiar with his belief that there are two layers — a primary world and a secondary world — that suspend our disbelief so we can become fully immersed in a fantasy setting?”

“No,” I said, but I was thoroughly intrigued.

And now, here I am, a two-time award-winning author writing this post more than a decade later to once again reexamine Tolkien’s basic concepts when it comes to worldbuilding.

What is Worldbuilding?

Worldbuilding is the construction of an imaginary setting in fiction. It can be as small as a room where an entire story takes place, or as massive as an entire multiverse.

For many sci-fi and fantasy writers who create their own fictional realities, worldbuilding goes much deeper than simply drawing a geographical map. It includes history, linguistics, anthropology, biology, ecology, technology, and even physics.

There are two methods of world-building: top-down and bottom-up.

Top-down worldbuilding is when the creator starts with a general overview such as geographic layout, climate, history, and inhabitants, and then becomes more detailed. The land is broken up into continents, nations, territories, and towns. Cultures, languages, and technologies are established. It all starts with a wide lens and then zooms in.

Bottom-up worldbuilding is when the creator starts with the specific location(s) needed for the plot, such as a specific town. This one place and the people who live there are developed in great detail. Over time, the rest of the world is developed around this focal point.

Some writers (like me) use a combination of these methods.

In order for fantasy worldbuilding to be successful, there must be logical rules even if there’s also magic and elements of reality that don’t exist in the real world. For example, you can build a civilization on an asteroid, but in order for readers to believe in this imagined reality, you must also provide a reasonable explanation for how your people get oxygen, obtain food and drinking water, deal with waste management, et cetera.

When the imaginary world is developed with enough layers and consistent fundamental rules, readers can be fully immersed without questioning the plausibility of the fictional world.

Legendary worldbuilder J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, referred to this absorption as “Secondary Belief.”

Primary World and Secondary World Fantasy

Tolkien differentiated the real world (Primary World) from the imaginary world that exists within the author’s mind (Secondary World). Many people use the terms “in-universe” and “out-of-universe” today.

Tolkien spent almost six decades constructing his secondary world of Middle Earth. In his essay “On Fairy-Stories,” he wrote:

Children are capable, of course, of literary belief, when the story-maker’s art is good enough to produce it. That state of mind has been called “willing suspension of disbelief.” But this does not seem to me a good description of what happens. What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside. If you are obliged, by kindliness or circumstance, to stay, then disbelief must be suspended (or stifled), otherwise listening and looking would become intolerable. But this suspension of disbelief is a substitute for the genuine thing, a subterfuge we use when condescending to games or make-believe, or when trying (more or less willingly) to find what virtue we can in the work of an art that has for us failed.

“On Fairy-Stories” by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1939

In my research on the topic, I discovered that there are multiple ways to view the primary vs. secondary worlds.

An example would be Tolkien’s invented language Sindarin. Some would consider its primary-world history to be Tolkien’s process of developing the language in real life, while its secondary-world history would be the fictional history of how the language evolved from Primitive Elvish.

However, other articles refer to the primary world as a real-world setting — our world, history, and elements versus the imagined world.

This shift of perspective brings us to the friendship of Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, the author of The Chronicles of Narnia.

Middle Earth vs. Narnia

Tolkien and Lewis were close friends, and they belonged to a writers’ group called the Inklings in the 1930’s and 40’s. But, even though both of their fictional worlds have gone down in history and been wildly popular, Tolkien hated Narnia.

In part, he disliked allegories, and he also felt that Narnia was a disorganized, inconsistent mess of various myths. He didn’t believe that Father Christmas should be mixed in with creatures from Greek and Roman mythology along with dragons, talking animals, and other mythological creatures in what he perceived to be a poorly conceived mishmash.

Tolkien had crafted Middle Earth with great care, and it stood on its own as a solo creation completely separate from the primary world. Middle Earth is not part of our reality. There are no rabbit holes or wardrobes connecting Middle Earth to the real world, nor are there any references to the primary world. The two stand apart without any overlap.

Lewis, on the other hand, blended both primary-world and secondary-world elements into his work. He used primary-world phrases, myths, and details in Narnia, even creating “bridges” in his stories that allowed children from the primary world to venture into the secondary world of Narnia. From Tolkien’s point of view, this unholy union broke the Secondary Belief.

While Tolkien detested Narnia, he was clearly wrong about its certain doom as a failed creation. The tales became one of the most beloved and successful children’s series, and others, like Harry Potter, have followed a similar structure by allowing the primary and secondary worlds to exist within the same place.

This shows how the primary world can be regarded in different ways. In the first discussion, we talked about the primary world being the creation of Sindarin here in the real world as Tolkien studied linguistics and crafted the language. Then, we explored the primary world as a real-world setting and elements penned into a novel.

And yet, my English teacher and I talked about the primary world in a third, different context.

Primary and Secondary Details in a Fictional World

Let me prelude this next section by mentioning that for reference, Shadow Rider was a high fantasy that was set up like Middle Earth rather than Narnia, completely segmented as a standalone world disconnected from the primary world.

However, my teacher viewed the primary world, at least in this discussion (as well as I can remember), not as its own separate entity, but rather the layer of real-world details that are identical in the fictional world as well.

For example, in my imagined world of Sercosia, the sky is still blue, the trees still drop their leaves in the fall, and the human anatomy is the same as yours or mine. The weather and ecology in certain habitats match what you would find here on Earth if you hiked through the mountains, deserts, or Great Plains.

It’s these types of details, he said, that help to enable suspension of belief when the fantasy elements are introduced. We accept that rain falls from the sky and gravity works the same way we know it to. But woven into these primary-world details are the secondary ones, such as magic spells and strange creatures and new languages, and that is where fantasy worldbuilding comes into play.

As I understood him, good worldbuilding happens when the laws of the secondary world can fit seamlessly within the laws of the primary world to create one fictional place that seems perfectly logical, as long as the rules established in the setting remain consistent.

A fictional world that is completely redesigned so almost every single aspect is alien would struggle to pull the reader in with any reasonable Secondary Belief. Our minds need at least some familiarity to connect with before they can be broadened to accept the fictional elements.

The primary and secondary worlds in this analysis are not separate places (Middle Earth vs. the United Kingdom), but rather, layers of details that stitch a fictional world together. If a writer is going to convince you that magic is real, that process starts by first agreeing on other laws of physics that you know to be true, then adding new rules into the mix.

That doesn’t mean the primary-world details are always the same. In Shadow Rider, I kept the sky blue. It’s the same sky you would see if you stepped outside and looked up, albeit with different stars and constellations. However, in my other fantasy series, Chronicles of Avilésor, the sky in the Ghost Realm is rarely blue. It changes colors based on atmospheric gas concentrations and winds.

In one setting, the sky is a primary-world detail, and in the other, it’s a secondary-world detail. At least, as far as this particular viewpoint of the primary world and secondary world goes.

Fantasy Worldbuilding Tips

A lot of work goes into fantasy worldbuilding, but for those of us who enjoy it, that’s half the fun of writing in the fantasy genre!

If you’re just getting started, here are some great worldbuilding tips to help as you begin to craft your secondary world:

- If you are using existing cultures as inspiration for your secondary world, due diligent research. Adaptations to real-world customs should be intentional rather than an oversight.

- Keep it simple. Feel free to fill a notebook with ideas, but when writing your manuscript, most of those notes should be for personal use only to help you remember details and keep everything straight. (Read: The Iceberg Theory) If something is too complicated, your reader is likely to get lost.

- Be detail-oriented. Engaging the senses is often helpful for bringing secondary-world elements to life for a reader. What does the fur of a fictional creature feel like? How does an imagined flower smell?

- Create a status quo. Societies have a hierarchy system in some form, whether it’s money, physical appearance, supernatural abilities, magic usage, etc.

- Determine the technology level of your world and then make sure any tools or gadgets are within that level (unless you can otherwise explain why they aren’t).

- Consider how religion impacts your society. There’s no doubt religion has shaped our world, so how would it have shaped yours? Are your people atheists? Monotheists? Polytheists? How do cultures with different religious beliefs interact with one another?

- Think about what kind of clothing your people will wear. If it’s based on an historical period from the primary world, make sure the details you include are accurate.

- Above all, BE CONSISTENT. This is the most important rule of worldbuilding. Inconsistency with details is the fastest way to suspend Secondary Belief.

Final Thoughts?

I enjoyed diving into the various interpretations of primary and secondary worlds! Each viewpoint offered a different perspective of how fantasy worldbuilding works in relation to what we know and accept here in the real world.

Any thoughts you’d like to add to the discussion? Please share in the comments!

Love worldbuilding sci-fi fantasy? Check out my award-winning Chronicles of Avilésor: War of the Realms series if you enjoy a blended primary and secondary world with supernatural + paranormal elements.

I'm an award-winning fantasy author, artist, and photographer from La Porte, Indiana. My poetry, short fiction, and memoir works have been featured in various anthologies and journals since 2005, and several of my poems are available in the Indiana Poetry Archives. The first three novels in my Chronicles of Avilésor: War of the Realms series have received awards from Literary Titan.

After some time working as a freelance writer, I was shocked by how many website articles are actually written by paid "ghost writers" but published under the byline of a different author. It was a jolt seeing my articles presented as if they were written by a high-profile CEO or an industry expert with decades of experience. I'll be honest; it felt slimy and dishonest. I had none of the credentials readers assumed the author of the article actually had. Ghost writing is a perfectly legal, astonishingly common practice, and now, AI has entered the playing field to further muddy the waters. It's hard to trust who (or what) actually wrote the content you'll read online these days.

That's not the case here at On The Cobblestone Road. I do not and never will pay a ghost writer, then slap my name on their work as if I'd written it. This website is 100% authentic. No outsourcing. No ghost writing. No AI-generated content. It's just me... as it should be.

If you would like to support my work, check out the Support The Creator page for more information. Thank you for finding my website! 🖤

2 thoughts on “Fantasy Worldbuilding: Tolkien’s Primary and Secondary Worlds”

That was very interesting and I’m glad I read it. I never really stopped to think what an author must have gone through to create the world that I was reading about. It got me to reflect about some of my favorite fantasy series and which type of world the author had built.

Thank you! I’m really glad to hear that the article got you thinking! It’s an intriguing subject, and there’s definitely an art to it.

Comments are closed.